![Main heading: The Music of Gustav Mahler: A Catalogue of Manuscript and Printed Sources [rule] Paul Banks](../../images/General%20Heading3.jpg)

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

Index of Works |

|

||||||

|

Site Map |

|

||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

Index to this page

Notes

|

|||||||

Josef Weinberger

Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen

The founder of the company, Josef Weinberger (1855–1928), was born in

Lipto St. Miklos

in

Moravia, but moved to Vienna with his family in the mid 1860s. They

formed part of the enormous wave of immigration into Vienna that

followed the demolition of the city walls, and the improved civil rights

for Jews living in the Habsburg lands after 1860. Josef's father was a

goldsmith who ensured that his son had a commercial training, but

Weinberger had a keen interest in music, being a capable pianist and

singer. In 1885 he joined forces with Carl Hofbauer to form 'Josef

Weinberger and Carl Hofbauer' art and music dealers, at 34

Kärntnerstrasse, Vienna. Their first entries in the Hofmeister

Monatsbericht appeared in the March-April issue of 1886 and included

Franz Roth's, Das tanzende Wien, (Walzer f. Pfte.) Op. 336; over

the next four years eighty-four titles were listed, the last appearing

in April 1890. By that date the two partners had split up. As early as

1889 Weinberger had established a separate firm of his own based in

Leipzig – perhaps with the help of Friedrich Hofmeister (though not

initially with Carl Günther, as stated in

HYJW, 7) – the main impetus being a desire to secure improved

international copyright protection: at the time Austro-Hungary was not a

signatory to the

Berne Convention, but Germany was.

(This strategy seems to have been adopted in the the 1890s by other

Viennese music publishers, including Robitschek (c.1894) and Hofbauer (c.1895)) The first of

Weinberger's Leipzig publications to be listed in the Monatsbericht

appeared in October 1889, and on 1 January 1890 he opened his own

premises at 8-10 Kohlmarkt in Vienna and it was from there that

Weinberger managed the company.

in

Moravia, but moved to Vienna with his family in the mid 1860s. They

formed part of the enormous wave of immigration into Vienna that

followed the demolition of the city walls, and the improved civil rights

for Jews living in the Habsburg lands after 1860. Josef's father was a

goldsmith who ensured that his son had a commercial training, but

Weinberger had a keen interest in music, being a capable pianist and

singer. In 1885 he joined forces with Carl Hofbauer to form 'Josef

Weinberger and Carl Hofbauer' art and music dealers, at 34

Kärntnerstrasse, Vienna. Their first entries in the Hofmeister

Monatsbericht appeared in the March-April issue of 1886 and included

Franz Roth's, Das tanzende Wien, (Walzer f. Pfte.) Op. 336; over

the next four years eighty-four titles were listed, the last appearing

in April 1890. By that date the two partners had split up. As early as

1889 Weinberger had established a separate firm of his own based in

Leipzig – perhaps with the help of Friedrich Hofmeister (though not

initially with Carl Günther, as stated in

HYJW, 7) – the main impetus being a desire to secure improved

international copyright protection: at the time Austro-Hungary was not a

signatory to the

Berne Convention, but Germany was.

(This strategy seems to have been adopted in the the 1890s by other

Viennese music publishers, including Robitschek (c.1894) and Hofbauer (c.1895)) The first of

Weinberger's Leipzig publications to be listed in the Monatsbericht

appeared in October 1889, and on 1 January 1890 he opened his own

premises at 8-10 Kohlmarkt in Vienna and it was from there that

Weinberger managed the company.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the developing Weinberger catalogue was the commitment to Czech music, and from April 1893 to August 1894 the Hofmeister entries were almost all by Smetana (various publications of Dalibor and Hubička as well as overtures) and Vilém Blodek (V studni); later additions included Tajemstvi (1895) and Libuše (1897). Otherwise most of the repertoire was of popular music for various combinations, not least military bands, with von Suppé figuring prominently from 1895 onwards.

The mid 1890s also saw significant enlargements of the Weinberger catalogue through the acquisition of other publisher's lists: in 1894 the ancient firm of Artaria, then in 1895 items from the Kratochwill catalogue and over 1,500 works from the Kratz catalogue of theatrical works. This latter acquisition included a number of works with international performing rights, which encouraged Weinberger to open a Parisian branch in 1896, but it also reflected a shift in Weinberger's publishing interests towards theatrical music generally. Another major step in that direction was taken in 1897, when the entire theatrical catalogue of Gustav Lewy – which included the stage works of Johann Strauss the younger and Millöcker – were taken over (with the Strauss performing rights following in 1899), and in the three following decades Wolf-Ferrari, Leo Fall, Emmerich Kálmán and Lehar were also published by the firm.

Although Austro-Hungary was slow to recognise the importance of international copyright (the Austrian Republic finally joined the Berne Convention in 1920), a far-sighted law of its own established performing rights for non-theatrical musical works was promulgated on 26 December 1895. When, as a consequence, the national Gesellschaft der Autoren, Komponisten und Musikverleger in Wien (AKM) was established in 1897, Weinberger was elected President and in 1910 an honorary member. This enhanced his contacts with the central government:

|

In 1898, acting at AKM's request, the Ministry of Culture and Education established a council of experts on musical matters with a six-year brief. Weinberger served on it with such practising musicians as Mahler, Kienzel and Richard Heuberger. Weinberger's next public task was to prepare a report for the Ministry of the Interior on the advisability of Austro-Hungary joining the Berne Copyright Convention. Then, at the request of the Ministry of Justice, he carried out research personally in Paris into all decrees and laws concerning copyright and related subjects since the French Revolution (HYJW, 11). |

How and when Mahler's association with Josef Weinberger commenced is not certain, but within months of Mahler's arrival at the Hofoper in Vienna he signed a contract for the publication of the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, on 27 September 1897 (reproduced in DM2, p. 91; GMBsV, 108–9) and we know that Weinberger was in close contact with Mahler's concert agent, Gustav Lewy, because at that moment he was negotiating to purchase Lewy's theatrical catalogue. It is perhaps no coincidence that within two months, on 11 November 1897, Mahler joined AKM as a composer member (no. 120): it was not required by his new contract, but Weinberger may have encouraged this decision.¹

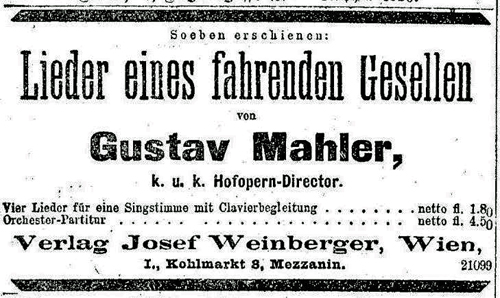

The contract for the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen was signed somewhat late in the day: the engraving of the voice and piano version was well under way, and uncorrected proofs, sent to establish US copyright, were received at the Library of Congress by 20 September. (This manoeuvre was essential since neither Austria nor the United States were signatories to the Berne Convention). Production proceeded relatively smoothly, and both the voice and piano version and the full score were listed in the December 1897 issue of the Hofmeister Monatsbericht, and were advertised in the Neue freie Presse on 5 December:

Fig. 1

Neue freie Presse, 11956 (5 December 1897), 17

By that time discussions, led by Guido Adler, about a possible subsidy to support the publication of Mahler's First and Third Symphonies (and the parts of the Second) by the Erste Wiener Zeitungsgesellschaft (EWZG), which owned the printing firm Jos. Eberle & Co. with its well-established music department, were under way and were concluded successfully in 1898. Before selling his firm to EWZG, Eberle had already acquired the rights to some of Bruckner's symphonies and masses, as well as smaller works, published them 'In Commission' through another Viennese publisher (for whom he was the main music printer), Bernhard Herzmansky (Ludwig Doblinger). It appears that initially it was thought that the rights to the Mahler symphonies would be acquired by EWZG, and issued in the same way, through Doblinger (see HLG1, 466); in the event it was Weinberger (for whose firm Eberle also undertook most of the music printing) who was initially responsible for their distribution from 1899 (Symphonies No. 1 and 2) and 1902 (Symphony No. 3). In addition EWZG took on other works by Mahler – the Lieder aus Des Knaben Wunderhorn (1899), Das klagende Lied (?1902) and the Fourth Symphony (1902) – and all except the last (which was distributed by Doblinger), appeared under the Weinberger imprint.

Weinberger and Universal Edition

The details of the creation of Universal Edition are still not entirely certain. One version of the narrative is presented in the 1985 centenary history of Josef Weinberger (HYJW, 13–14):

|

Since 1896 Weinberger, together with Bernhard Herzmansky of Ludwig Doblinger, and Adolf Robitschek, had been planning an edition of universal appeal to challenge Peters and secure for Vienna the unquestioned title of the world's music publishing capital. The plans crystallised in 1900 with the creation of the Universal Edition, with a primary target of 1,000 volumes, predominantly the popular classics, but interspersed with new works. Weinberger and other publishers licensed it to reprint some of their works or transferred rights against payment. In order to ensure the livelihood of the new edition, Josef Weinberger himself guaranteed the purchase of substantial quantities. He helped put together a consortium of like-minded people to finance the edition: the Austrian Länderbank was the principal member, and placed an order with the printer Eberle and Co for the main body of the edition, a massive total of 65,000 printing plates. The edition was of excellent quality and by July 1901 the catalogue already consisted of 250 volumes. Universal Edition's first offices were at Weinberger's in Maximilianstrasse, and he was appointed chief administrator. The new enterprise flourished. The financial implication of no longer having to spend currency on imported goods was not lost on the Ministry of Education, which issued an edict in July 1901 [5 July 1901] to all music schools and conservatoires, prescribing the use of the new publications. Published also in English and French, the edition quickly won recognition abroad. The classical repertoire was covered within a year and modern composers' works began to be added. Weinberger ceded to it almost all his Mahler publications, (to the subsequent bitter regret of his successors!) and in 1904 he arranged for Universal to buy the Munich house of Josef Aibl, the publisher of Richard Strauss' early works. But perhaps his greatest contribution to the new enterprise was his secondment of one of his senior employees, Emil Hertzka, to be Universal's general manager. This bearded giant was to become one of the greatest, almost visionary, music publishers of all time, to Universal Edition's enduring benefit. |

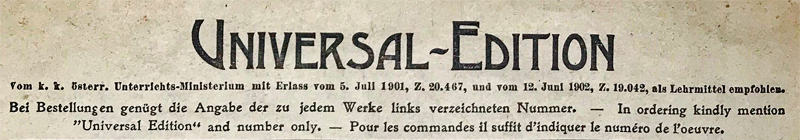

The likelihood is that Weinberger's earlier links to the government helped to facilitate the negotiations that culminated in the edict of 5 July 1901 (Z. 20.467) and that of 12 June 1902 (Z 19.042 – both referred to on early UE wrappers: see Fig. 2 below). Moreover, his dealings with the Strauss family through his acquisition of the publication and performing rights to the theatrical works of Johann Strauss II (1897–9) no doubt brought him into contact with Josef Simon, Strauss's brother-in-law, the banker who became one of main financiers of the new publishing house. Having played a significant role in its establishment, Weinberger proceeded to run the new business for the first six years of its existence.

Fig. 2

Mahler: Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen, PV52a,

back wrapper, verso

Leipzig: C.F. Kahnt Nachfolger / Vienna:

Universal-Edition, 1910

Despite the assertion to the contrary in the company history (see above), it must have been the Erste Wiener Zeitungsgesellschaft (EWZG), another of the founders of Universal Edition, that in 1906 licensed the new company to distribute study scores of the first four Mahler symphonies (a format Weinberger and Doblinger had not employed for these works) and the piano duet arrangements (which those firms had sold under their own imprints). It is not clear what impact these new licences had on the distribution of the piano duet versions: what did Weinberger and Doblinger do with their remaining stock? Copies of the arrangements with the imprint pasted over with a 'Universal Edition' label survive (see the relevant bibliographic descriptions in the Catalogue). Did Weinberger and Doblinger retain some or all of their stock, and continue to sell such stock under the original imprints, or with 'Universal Edition' paste-overs?

The evidence supplied by initial entries for

these duet arrangements in the relevant UE

Verlagsbuch is not illuminating:

Ed. No.

Work

Format

Date of order

No. of copies

Date of receipt

No. of copies

947

Symphonie I / D-dur

Kl. 4/ms

1906.11.09

150

1906.11.10

150

949

Symphonie II

/ C-moll

Kl. à 4 mains

1906.11.09

150

1906.11.10

155

951

Symphonie III

Kl. à 4 mains

1906.11.09

150

1906.11.10

150

953

Symphonie IV / G-dur

Kl. à 4 mains

1906.11.09

150

1906.11.10

150

Table 1

The issue here is whether these initial entries were for a new print run, or merely recorded the transfer of stock to Universal Edition. On the one hand the layout and content of these entries is almost precisely what would expect for a normal printing, and the fact that the number of copies ordered is consistent reinforces the reading that these entries are for the first UE printing of the arrangements. However, these entries have two notable features: that they are all made in pencil, which is very unusual, and the fact that Eberle & Co. appears to have been able to supply 655 copies of four different publications within a day of the order (on the face of it, rather implausible, though by this date the business had substantial specialist facilities for music printing). The latter features might lend some support to the view that these entries refer to the request for and delivery of stock from Weinberger and Doblinger (and since it seems unlikely that in three cases exactly 150 copies remained in stock) some copies were retained by the original distributors. However, on balance, it seems more likely that the most obvious reading is the correct one: that these entries refer to the first printing of the arrangements 'In die Universal Edition aufgenommen'. What happened to the old stock remains unclear, but it is worth noting that these arrangements were all announced in the January 1906 issue of the Hofmeister Monatsbericht (see also the relevant entries in this catalogue), apparently ten months before the first printing of the new UE issue. So at the very least UE would have needed some of the old stock - presumably with their own paste-overs affixed - to satisfy any orders generated by the Monatsbericht listing.

This first phase was apparently to be followed in 1908 by a second phase of revised publishing arrangements relating to Mahler's music. The UE Verlagsbuch reveals that a block of four UE Edition numbers were assigned to works by Mahler in that year:

| Ed. No. | Work | Format |

Date of order |

Date of receipt |

No. of copies |

|

1690 |

Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen |

Voice & Piano |

1908.10.30 |

1908.11.27 |

200 |

|

1691 |

Des Knaben Wunderhorn, vol. 1 |

Voice & Piano |

1910.03.14 |

1910.03.18 |

100 |

|

1692 |

Des Knaben Wunderhorn, vol. 2 |

Voice & Piano |

1910.03.14 |

1910.03.18 |

100 |

|

1694 |

Das klagende Lied |

Vocal score |

1910.02.08 |

1910.02.30 |

30 |

| Table 2 | |||||

The immediately adjacent items in the Edition number sequence on either side of this block are in a fairly consistent chronological order (the next two items were first ordered in September 1908), so it appears that after the edition numbers were assigned to the Mahler publications there were delays or postponements in the ordering of all four. Of these the first, and least delayed, was the song cycle owned by Weinberger; the other three items were works published by Eberle but licensed to Weinberger, and the first UE printings were not ordered for two years. The reason for delay is not clear (see the Eberle-EWZG page for some possible explanations). One unusual feature of the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen entry is the pencil note 'Sämtliche Druckkosten zahlen wir'. No equivalent note appears in entries relating to issues licensed from EWZG, so it would appear that Weinberger had negotiated a different (and probably favourable) financial arrangement for himself. Five re-prints followed in 1909–1915 (with the first issue, making a total of 1300 copies) but a print order for a further 200 copies, on 14 October 1915 is crossed through and there is no corresponding record of any copies received; another pencil note records 'Aus dem Katalog gestrichen 1916' implying that Weinberger had revoked the licensing arrangement.

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2258-0267

©

2007-21 Paul Banks | This page was lasted edited on

20 May 2021

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2258-0267

©

2007-21 Paul Banks | This page was lasted edited on

20 May 2021