![Main heading: The Music of Gustav Mahler: A Catalogue of Manuscript and Printed Sources [rule] Paul Banks](../../images/General%20Heading3.jpg)

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Index of Works |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Site Map |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Adaptations and/or new arrangements for Das Volkslied

| [Adaptations of existing music and/or new arrangements of folksongs for Das Volkslied] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Early 1885 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The work – „Volkslied“: Ein Gedicht mit Liedern, Chören und lebenden Bildern von S.H. Mosenthal, mit Musik von Franz Doppler – as presented in Kassel, consisted of eleven sections:¹ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1 'Old German Bard Songs' (chorus) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

2 'Minne court in Provence', troubadour song (tenor) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

3 'Ännchen von Tharau' (chorus) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

4 'Neopolitan improvisation', Italian canzonetta (soprano) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

5 'Homesickness': Herz mein Herz, warum so traurig? (soprano) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

6 'Gaudeamus igitur' (chorus) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

7 'Die Loreley' (tenor) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

8 'O du himmelblauer See' (duet) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

9 'Taking leave from home': Es ist bestimmt in Gottes Rath (chorus) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

10 'Heil dir im Siegerkranz' (chorus) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

11 'The Folk Songs' (apotheosis): the different nations pay tribute to the muse of the folk song (soloists and chorus) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Salomon Hermann von Mosenthal (1821–1877): Das Volkslied | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mahler version: unknown Doppler version: Fl 1–2 (=picc 1–2 (on stage,

later in the pit, No. 5)), ob 1–2 ([2?] = ca), cl 1–2 in A/B Hn 1–4 in F (3 players

onstage, No. 6; in E Timp, sd (off-stage, later in the pit, No. 5), bdrum, tambourin, tr Harp 1–2 (one on stage in Nos 2, 7; one off-stage in no. 4) Harmonium (on-stage, No. 7) Strings

Solo voices: tenor (No. 2); tenors and basses off-stage (No.3) Chorus (male voices, off-stage, No. 3) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Unknown |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

No manuscript of any of Mahler's revisions and/or additions has been located and they are currently presumed lost. An incomplete[?] copyist's[?] full score of (some of?) Franz Doppler's original music (DVCFD) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

None |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chronology | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Das Volkslied - the Urfassung (1868) The Vienna Version (1876) The Hamburg and Kassel Versions (1884, 1885) The Prague Version (Alfred Klaar, 1887)

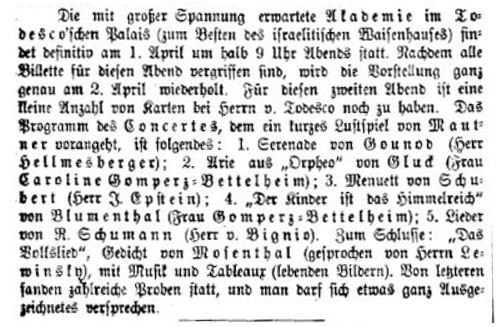

The Dienst-Instruction für den Musik- und Chor Direktor des Königlichen Theaters zu Cassel – which detailed Mahler's duties and responsibilities at the Theatre – included a number of clauses (§§7–9) that required him to provide, when necessary, adaptations or arrangements of existing music or newly-composed works.² Thus he was involved in an adaptation of Das Volkslied, an occasional work by the Austrian poet S.H. von Mosenthal (1821–1877), to be performed for the benefit of the theatre's pension fund. Although this theatre piece seems to have been first published in 1878,³ it had been staged in Vienna nearly a decade earlier, at two benefit performances in support of the Jewish Orphanage, on 1, 2 April 1868:

Fig. 1

This was the first of a number of occasional performances (more than thirty) in Austro-Hungary and Germany at fund-raising events for a variety of good causes organised intermittently up until 1902: after Mosenthal's death in 1877 the content of the entertainment was modified, often radically, by the production teams involved. Das Volkslied - the Urfassung (1868) No autograph or early source for the text of Mosenthal's 'Gedicht mit Liedern und Bilden' dating from before 1878 has been located. The relevant note in the 1878 printing records that just before his death he had assigned it for publication in the annual Deutsches Künstler-Album (Düsseldorf: Briedenstein und Baumann) and it seems probable that the text offered to Briedenstein and Baumann would have been substantially that printed in the Gesammelte Werke. However, the newspaper announcement cited above (Fig. 1) indicates that the work dated from a decade earlier, and had been performed at least once, at a charity event organised by the industrialist and banker Eduard von Todesco (1814–1887). This was given at the Palais Todesco (on the Ringstrasse, opposite the soon-to-open Hofoper) and was covered by a few local newspapers: from these reports it becomes clear that in several respects what was performed in 1868 differed from the text published a decade later (see Fig. 2 below). The 1878 version provides information about the desired musical content and in particular indicates that an orchestral accompaniment is envisaged. However, one reference in a report on the first performances (Wiener Sonn- und Montags-Zeitung) implies that the accompaniments were provided by a piano and none of the other press commentaries contradict that implication. Although all the reviewers emphasised that a considerable amount of money was expended on this production, they also comment on Todesco's immense wealth, so perhaps other factors – ease of rehearsal, scheduling and the performance space used – may have crucial in the decision to opt for a piano accompaniment. It is also notable that the original version was shorter – the seventh tableaux ('Loreley') and the Schlußtableau were later additions – the third and fourth were originally heard in reverse order, and, unless the press representatives were inattentive (or had left early) some of the musical components in the final version of the eighth tableau – Ungarischer Czardas, Böhmische Volksweise, Russische Volkslied and the Radetzky Marsch – were not yet included. Even more striking is the change of subject-matter in the fifth tableau: originally its celebration of freedom to the accompaniment of the Marseillaise might have caused the 'conservative millions in the room great consternation' (Wiener Sonn- und Montags-Zeitung). The replacement tableau, a celebration of a French-born Field-Marshall, Prinz Eugen (1663–1736), in the service of the Austrian Hapsburgs avoided any hint of political radicalism and this apparent shift in the historico-political alignment of the entertainment was reinforced by the inclusion of the Radetzky March in the new closing scene.

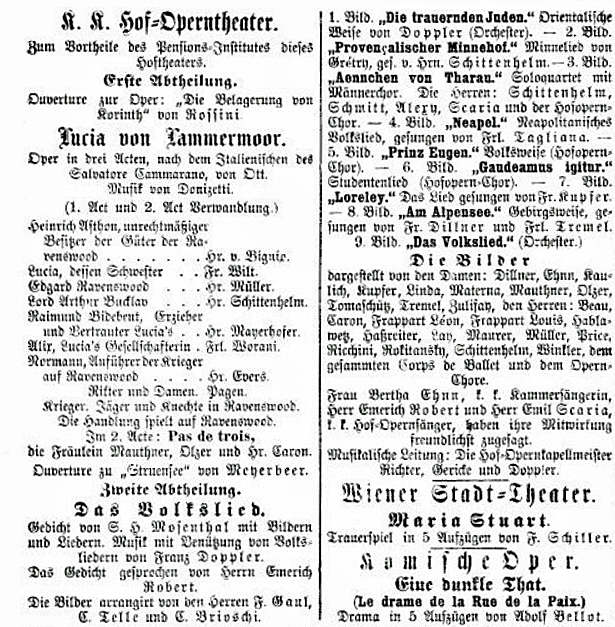

That the two creators of the most ambitious item in the programme of the 1868 fund-raising event were closely connected with the theatre (and specifically opera) in Vienna no doubt contributed to Das Volkslied having an after-life. Mosenthal (1821–77), born in Kassel, had moved to Vienna in the 1840s and from 1849 was a member of the Austrian civil service while following a parallel career as a dramatist and opera librettist. In the latter role the success of Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor (Nicolai: Vienna, 1849), established his reputation from the outset and was followed onto the Viennese stage by Die Königin von Saba (Goldmark: Vienna Court Opera, 1875 (17 performances)) and Die Folkunger (E. Kretschmer: Vienna Court Opera, 1876 (4 performances)).¹⁵ Meanwhile, on 12 January 1867 Franz Gaul (1837–1906) had been appointed the head of design department (Ausstattungswesens) at the Court Opera.¹⁶ In 1876 two performances in aid of the Pension Fund of the Court Theatres were announced, the first of which (23 December) included a performance of Das Volkslied:

Fig. 3

The comparison of this listing with that of the 1868 version (see Figs 2 & 3) makes it clear that a number of changes were made that reflect the extensive musical and scenic resources available to the Hofoper. Three senior members of staff – Gaul, Karl Telle (ballet master) and Carlo Brioschi (scene painter) – were involved in the production, along with Franz Doppler (composer, flautist and ballet conductor) who provided the orchestral score.¹⁷ The extent to which the latter was based on the music of the first production has not yet been ascertained. Presumably the revisions and new additions were undertaken by all four as employees of the Hofoper (as was the case when Mahler adapted the music for Kassel in 1885) and the necessary sets, costumes, scripts and musical materials produced in-house. The production was quickly loaned to the Carl-Theater in Vienna for a charity performance (8 February 1877) before being revived at the Hofoper for another Christmas benefit performance, on 23 December 1877. One advertisement for the latter (Wiener Zeitung) reproduces the details of the work as publicised in 1876 (see Fig. 3 above), except in one respect: the first scene is described as '1. Bild. „Saul und David.“ Orientalische Weise von Doppler (Orchester)'. A clue to the motivation behind this apparently innocuous change may perhaps be provided by an anonymous review of the 1868 performance that is inflected with racial antipathy:¹⁸

Whatever the reason for the modification, it was not adopted in the published version of the text of the work, although it was retained in some later theatrical performances. The explanation for this may be entirely practical: for some years an important source for pre-existing designs, scripts and musical materials would have been the Hofoper in Vienna, which presumably loaned or hired out the set it had prepared for its own use. The Hamburg and Cassel Versions (1884, 1885) The first such loan/hire seems to have been to the K.K. Theater in Salzburg where two performances (probably both performed largely by amateurs, with professional support) were given in April 1881. No detailed information about the number or subject-matter of the tableaux has been traced, but such information is available for the first production outside the Dual Monarchy, given in Hamburg in March 1884,¹⁹ allowing for a comparison with the Vienna version, and the Cassel version of 1885:

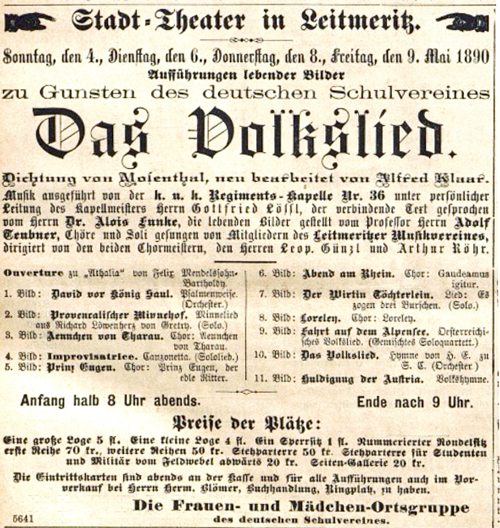

Although the Hamburg version (1884) expanded the piece with three additional tableaux (8, 9 and 11 (a tribute to the ruling house of the German Reich)), it appears to have retained the order and general content of the 1877 version, including Saul und David. However, the extent to which its final scene retained Austro-Hungarian musical elements from the Viennese version is uncertain. It seems that in part the Cassel version can be interpreted as further associating the work with the German Reich and specifically German culture by excluding or minimising references to Jews (tableau 1) or Austro-Hungary (tableaux 5, 8 and 9). Where exactly within Cassel's political and artistic hierarchies this adjustment was initiated is not clear. According to de La Grange the work was performed 'with music orchestrated by Gustav Mahler on the basis of early folk songs, and arranged for the Cassel stage by Otto Ewald'.²⁷ The two men had both been connected with the creation of the similar entertainment, Der Trompeter von Sakkingen, performed at a charity event at the Cassel opera the previous year. Ewald (1848–1906) was a multi-talented man of the theatre, trained in the visual arts and music. After working as a buffo tenor and comic actor in various theatres²⁸ he joined the Königliche Schauspiel in 1871; by 1885 he was 'Regisseur ... der Posse, Operette und Oper' and he retired in 1901. The Kassel Manuscript ([1885?]) A short description of this document, a copyist's manuscript of some of Doppler's music now in the collections of Universitätsbibliothek Kassel (2° Ms. Mus. 1186), was published in 1997;²⁹ a digitisation is available online,³º and a separate, more detailed description of the document and its contents is in preparation.

The original layer of the manuscript appears to be a fair copy of a version that in broad content followed the 1876 version as far No. 7. The function of the inserts A-C is unclear and a pencil note at the end No. 7 – 'Folgt Nr. 8' – suggests that they may have been omitted. With one exception (the use of the Russian Imperial Anthem in No. 9½) the remaining items in the Cassel score have no direct parallels in any of the other versions. It appears that the score may present two different endings, the earlier of which concluded with No. 9, and a subsequent variant that omitted the Weber extract and replaced it with Nos. 9½ & 11 (see also the further discussion below). In addition numbers have been added discretely in pencil above some bar lines from p. 39 onwards. These may be an indication of an alternative casting-off of the score, made in preparation for the preparation of a new copy. The revisions made in this manuscript do not obviously embody or even prefigure the content of the Kassel version as described by Schaefer and de La Grange, so its role - if any - in the creation of that variant is uncertain. Even if it played no direct role in the evolution of the version Mahler conducted, the Doppler version's use of instruments that moved between the pit and the stage (notably the trumpets in No. 5), serve as a reminder that this not uncommon feature of Mahler's later concert works had a well-established role in music written for the theatre. The bar counts included in Fig. 5 above do not include repeats of passages so marked in the score. This serves to emphasise the pragmatic approach adopted which, by using such repetitions, minimised the resources that needed to be expended on the preparation of the performing material, learning of, and rehearsals for a work that, by its very nature, was likely to receive a very limited number of performances in a run (the maximum traced so far is five (Hamburg, March 1884)). The Prague Version (Alfred Klaar, 1887)

At present, in the absence of access to any contemporary acting scripts or scores, it is not possible to propose firm identifications of the texts and music employed in all tableaux: the following partial account offers suggestions ranging from the conjectural to the firmly grounded. Provençalischer Minnehof The advert for the 1876 Vienna production (Fig. 3 above) identifies the musical item associated with the second tableaux as 'Minnelied von Grétry' and Hanslick, in his review of the 1876 performance, identifies this as Blondel's Romance from Grétry's Richard Coeur-de-Lion (1784), and criticises the attempt to pass it off as a Provencal folksong. Nevertheless it seems to have retained its place in later versions, including that by Klaar (see Fig. 6). Ännchen von Tharau A helpful and well-documented account of the history of the text and associated melodies (with transcriptions) is provided by the Historisch-kritisches Liederlexikon (HkLl; Universität Freiburg/DFG). The original 17-stanza Plattdeutsch text was written by Simon Dach (1605–1659), probably in 1636. A setting for voice, violin and continuo was published by Heinrich Albert (1604-1651) in 1642, but the song became better known through Herder's version in Hochdeutsch that was published in his Volkslieder (1778); a version was also published under the title Palmbaum in volume 1 of Des Knaben Wunderhorn (1806). Settings of Herder's version were published as solo songs in 1779 by Karl Siegmund Freiherr von Seckendorff (1744–1785) and in 1798 Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752-1814), and it may have been one of these that was sung by Henriette Tauber at the first performance of Das Volkslied in 1868 (see Wiener Sonn- und Montags-Zeitung). However in later performances it appears to have been performed in a four-voice version, almost certainly the very popular setting from 1827, by Friedrich Silcher. According to HkLl "In this version, Ännchen von Tharau developed into the epitome of popular male choir aesthetics of the 19th and 20th centuries and, in this sense, had a lasting impact on ideas about 'folk song'". Prinz Eugen, der edle Ritter HkLl provides a useful account of the text and music of the song, which was probably composed soon after the events it celebrates (the capture of Belgrade from the Ottoman Empire in 1717). In the mid-nineteenth century there was some debate about the metrical notation of the song, Ludwig Erk and Andreas Kretschmer favouring 5/4, others (including Friedrich Silcher) favouring an alternation of 3/4 and 2/4 and this is the solution adopted in the Doppler score. Nevertheless, versions of the song were also used as the basis for marches, including one by Josef Strauss (op. 186, 1865) composed for the unveiling of the statue to Prince Eugene by Anton Dominik Fernkom and Franz Pönninger in the Heldenplatz, Vienna. Gaudeamus igitur This internationally-known student drinking song attracted numerous composers in the nineteenth century, including Brahms (Akademische Fest-Ouverture, op. 80 (1881)) and Johann Strauss the Younger (Studenten-Polka, op. 263 (1862)). Noch ist Polen nicht verloren This is the opening line of a text written in 1797 by Jósef Wybicki (1747–1822) and set to music by an unknown composer under the title Mazurek Dąbrowskiego. Since 1926 it has been the official national anthem of Poland. The melody has been used or alluded to in a number of concert works, including Wagner's Polonia Overture (1836), Paderewski's Symphony in B minor (1903–08), and Elgar's Polonia, op. 76 (1915). The text is by Vasily Zhukovsky (1783–1859) and the music by Alexei Lvov (1798–1870). This may have been the Russian contribution to the original 1868 version. The only other reference to a Russian component is the Cassel manuscript, No. 9½, which shows the first eight bars of the hymn leading into the final twelve bars of Wacht am Rhein. The text was by Max Schneckenburger (1819–1849) and the music by Karl Wilhelm (1815–1873). The Cassel manuscript, No. 9½, is the only source to refer specifically to this song: it is preceded by the first eight bars of the national anthem of the Russian Empire. This number has every appearance of being an insert, raising the possibility that it was envisaged that Das Volkslied would be performed at some official or semi-official event at which both Empires would be represented. Mahler's contribution to the Cassel version Unfortunately the documentation of Mahler's involvement with the Cassel version is virtually non-existent. Hans Joachim Schaefer, who certainly drew on primary sources, did not mention the work in his first book about Mahler in Kassel (HJSGMK), and the reference in the second (HJSGMJ, 51), while tantalizing in its details, cites no sources:

The context of the two performances of the work in Kassel is unexplained, though it is certainly possible that one or both were in aid of some charitable cause(s), which might explain why a thorough overhaul of the music was deemed desirable or necessary.⁴⁴ On the other hand, they were given in evenings devoted to works that included spoken dialogue and music from the existing repertoire of the theatre, so may have been developed simply as a local addition to the theatre repertoire. Mahler's job description (Dienst-Instruction) required him to conduct all genres as required,⁴⁵ and, as the junior of the two staff conductors, he was presumably on the podium for the evenings of 20 April and 29 May 1885. The nature and extent of his creative input is unknown, but the musical numbers in Doppler's score are on a modest scale, ranging in length from 35–69 notated bars (repeats are rarely, if ever, written out in full, so as to minimize the amount of copying required). Mahler may have been more expansive in his treatment of the material, but his room for manoeuvre was presumably limited, if by nothing else, by the fact that the work's second performance would to be part of a quadruple bill (see above). No direct report of Mahler's view about Das Volkslied as a whole has been traced. It is striking that the 1868 version of the entertainment sought to offer an international survey of Volkslieder with only a modest emphasis on contributions from Habsburg lands. In this respect Mosenthal offered a relatively cosmopolitan celebration of the cultural significance of folksong, so one might wonder whether Mahler, the member only a few years earlier of the Aryan-orientated Saga Gesellschaft in Vienna, felt comfortable with Mosenthal's rather different standpoint.⁴⁶ Whatever the reason for the creation of a new, local version of Das Volkslied, there is evidence that by late March 1885 the working relationship between Mahler and Ewald was strained, and resulted in Mahler being penalised by the Intendant of the Theater, Baron von Gilsa. The issue was whether Mahler should have been present at a rehearsal for Act I of Schiller's Wilhelm Tell, in which Ewald (playing a shepherd) was off-stage, performing a song by Reinecke accompanied by a clarinet:⁴⁷

Mahler had already offered a different narrative: that he was called on during such rehearsals only rarely, and often had nothing to do. So, in this case he had agreed with the Chief Director that an earlier setting of the relevant text, by Anselm Weber,⁴⁸ would be used instead of Reinecke's number, and that he (Mahler) would therefore not be needed for the rehearsal. Whatever the truth of the matter, this incident does little credit to either of the protagonists, the artistic environment, or the levels of collaboration and support among colleagues in what seems to have been a very hierarchical and rule-bound institution. The extent to which its aftermath impacted on the final preparations and rehearsals for Das Volkslied seem not to have been recorded. However, even if was a troubled production it would have offered Mahler what was possibly only his second extended opportunity (following Der Trompeter von Sakkingen in 1884) to hear and assess his own orchestrations at rehearsal and in performance. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Provisional list of Performances | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2258-0267

©

2007-21 Paul Banks | This page was lasted edited on

20 August 2022

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2258-0267

©

2007-21 Paul Banks | This page was lasted edited on

20 August 2022