![Main heading: The Music of Gustav Mahler: A Catalogue of Manuscript and Printed Sources [rule] Paul Banks](../../images/General%20Heading3.jpg)

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Index of Works |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Site Map |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Symphony No. 2 in C minor

| Zweite Symphonie, C moll | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1888, 1893–4; revised 1895–1910 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1. Allegro maestoso. Mit durchaus ernstem und feierlichem Ausdruck [At end:] Hier folgt eine Pause von mindestens 5 Minuten |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

2. Andante moderato. Sehr gemächlich. Nie eilen. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

3. In ruhig fliessender Bewegung [At end:] Folgt ohne jede Unterbrechung der 4. Satz |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

4. „Urlicht” (aus „Des Knaben Wunderhorn”) Sehr feierlich aber schlicht (Choralmässig) [At end:] Folgt ohne jede Unterbrechung der 5. Satz |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

5. Im Tempo des Scherzo[.] Wild herausfahrend |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Movement 4: from Des Knaben Wunderhorn |

Movement 5: Klopstock: Die Auferstehung |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| January 1896 | March 1896 | Dresden 1901 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Fl 1–2 (= picc 3–4), fl 3–4 (= picc 1–2 ), ob

1–2,

ob 3–4 (= ca 1–2), cl 1–3 in A/B Hn 1–6 in F (+ hn 7–10 in 5th movement), tpt 1–6 in F (the score indicates 5, 6 can double as two of the off-stage tpt, but see the notes below), trb 1–4, cbtuba Timp 1–6 (two players; in 5th movement a 3rd player also uses 2 drums of 2nd timpanist), bd, cym, tam-tams 1–2 (high, low), tr, sd (doubled if possible), glock, 2 bells (of low, unpitched sound), rute (five percussionists) Harps 1–2 (doubled if possible), strings (at least some of the double-basses must have C) Off-stage (5th movement only): hn 1–4 in F (= hn 7–10 in the orchestra), tpt 1–4 in F/C (the score indicates that two may be played by tpt 5, 6 from orchestra, but see notes below); 1 timp, bd + cymb, tr Organ (5th movement only) Soprano solo (5th movement only), contralto solo (4th and 5th movements) Chorus (5th movement only)

The second flute requires B. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

80 minutes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Copyist's Manuscripts: full scores (?1894–5; 1895) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Copyist's Manuscripts: orchestral parts (1894–5) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arrangements: 2 pianos (1895) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arrangements: piano duet (?1898) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Autographs: orchestral part (1895) | Arrangements: piano solo; violin and piano (n.d.) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Printed Editions (1895–1920) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arrangements: vocal score (Urlicht) (1895; 1899; 1911) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arrangements: 2 pianos, 4 hands (1896; 1914) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arrangements: piano duet (1899; 1911) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arrangements: 2 pianos, 8 hands (1914) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arrangement for salon/small orchestra (1926) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Performance history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chronology | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Title and Programming Mahler conducted ten complete performances of the Symphony between 1895 and 1910, and in every case its title was entirely non-programmatic (see the list of performances for details). Mahler also gave three partial performances in the years 1895–6 and in the second of these, on 16 March 1896, the first movement was identified as „Todtenfeier” (I. Satz aus der Symphonie in C-moll für grosses Orchester), the only occasion Mahler used a programmatic title in connection with a performance. As the descriptions of the early printed editions demonstrate, none of the early publications included a programmatic element in the work's title. The earliest reference located so far to the work as the Auferstehungs-sinfonie appears in an anonymous review of a performance given at a Leipzig concert in memory of Mahler, conducted by Arthur Nikisch in the autumn of 1911 (NZfM 78/44 (2 November 1911), 625), but up to the end of 1914 such formulations appear to have been rarely used.

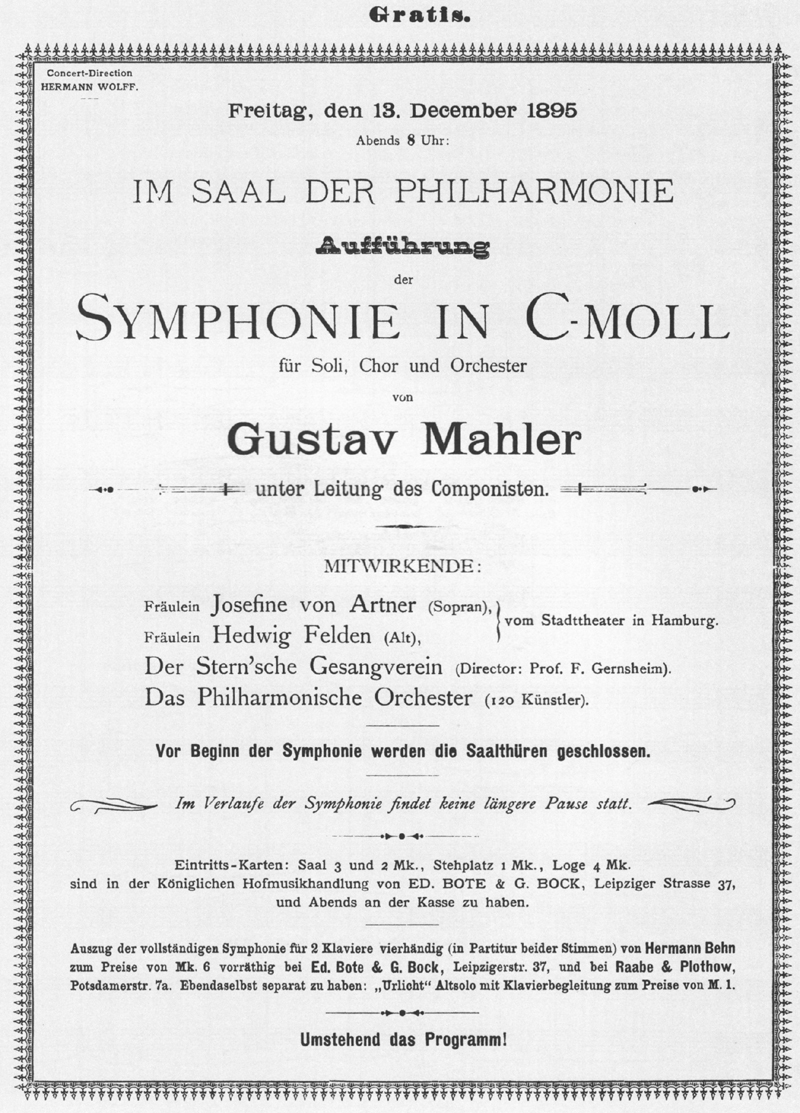

Handbill for the first complete performance There is evidence that although Mahler preferred to perform the Symphony at concerts in which it was the only work, four of his performances were in programmes that included other items: in three of these the Symphony was the final work. In all four cases Mahler may well have been responding to local or institutional traditions affecting concert duration, and both attitudes – his preferences and his pragmatism – were reflected in a letter responding to Oskar Fried's enquiry seeking advice about the programming of the work at a concert he was to conduct in Berlin on 8 November 1905 (GMUB, 52; GMUBE, 51–2):

Additional Literary Sources and Programmatic References a) The first movement clearly reflects the impact of Adam Mickiewicz's Dziady, in Sigfried Lipiner's translation as Todtenfeier (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1887): see SHMMT, 158–260 for an extended and insightful account. b) The first edition of the vocal score of Urlicht prints an additional text from Clemens Brentano's Gockel, Hinkel, Gackeleia beneath bb. 3–13 of the accompaniment: Stern und Blume! Geist und Kleid! Lieb' und Leid! Zeit! Ewigkeit! Many years later Anna Mahler told Henry-Louis de La Grange that Mahler delighted in reading this story to his eldest daughter, Maria (Putzi) (HLGIII, 690). The song was (probably) composed in 1893, but the autograph of the voice and piano version of the original solo song, prepared before Mahler decided to incorporate it into the Symphony, is lost, so it is not known whether the reference to the unsung text was part of that version; it does not appear in the earliest surviving autograph, Mahler's full score of the song. On the other hand the history of this unsung text reveals strong connections with the themes of death and resurrection that are central to the latter work. c) Edward Reilly pointed out that the connection between the text of Urlicht and the Last Judgement is made explicit in the closely related 'Vom jüngste Tage', the last poem of Jungbrunnen, a popular collection of German folksongs edited by Georg Scherer (ERSTS, 5–7). Mahler could have known this volume, or some of the earlier printed collections that contain versions of this text, and it is worth noting that the penultimate poem in Jungbrunnen is the Erntelied published by Brentano in the first volume as Des Knaben Wunderhorn. The later, much-expanded version of that text in his Gockel, Hinkel, Gackeleia is the source of the unsung quatrain discussed in note (b). d) The autograph score of the last movement (AF2) contains two programmatic headings. Der Rufer in der Wüste! on fol. 81v refers to passages in both the Old and New Testament – e.g. Isaiah 40:3 ('The voice of him that crieth in the wilderness'), Matthew 3:3, Mark 1:3, Luke 3:4 and John 4:3 – and relates to the horn solo in b. 43ff. Der grosse Apell on fol. 105r refers to 1 Corinthians 15:52 ('In a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trump: for the trumpet shall sound, and the dead shall be raised incorruptible, and we shall be changed) and relates to the passage starting at b. 449. These headings were retained in the early printed editions – PF1, PF1b, PF2, PT2p4 and PTp4 – and were printed in the movement description in the programme of the important performance, under Mahler, at Basel in June 1903; they were omitted from the first edition of the study score (PS1, 1906) and all later printings of it and the full score. a) The third movement incorporates an orchestral transcription of Mahler's Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt (Lieder aus Des Knaben Wunderhorn, No. 6). b) The fourth movement, Urlicht, was originally composed as an independent song and was later included as No. 12 in the published piano and voice and orchestral sets of the Lieder aus Des Knaben Wunderhorn. The orchestral song version is scored for a smaller ensemble than that used in the Symphony:

* [Hn 1–2] neben den beiden Harfen zu placieren Table 1 Quotations and Self-Borrowings a) The first movement (bb. 270ff.) and the finale (bb. 62ff.) quote the opening of the Dies irae plainchant. b) The head-motive of the E major theme in the third movement, bb. 257–60 is an allusion to the opening theme of the scherzo in Hans Rott's Symphony in E major. c) The closing bars of the third movement, bb. 577–81, quote the end of 'Das ist ein Flöten und Geigen' from Schumann's Dichterliebe, bb. 80–4. A number of the manuscript sources suggest that Mahler changed his mind about the order of the inner movements: the orchestral draft of the Scherzo (OD3; 16 July 1893) is numbered '2' and that of the Andante (OD2; 30 July 1893) is numbered '4'. If Urlicht was considered as another inner movement in the summer of 1893 and was therefore notionally no. 3, it is striking that the numbering sequence corresponds to the order in which the draft full scores of the three movements were completed (see the chronology above). However, there is other evidence that at that time Mahler had not definitively decided on the inclusion of the song in the Symphony: the first orchestral score of the song (DKW12 AF; 19 July 1893) identifies the work as aus des Knaben Wunderhorn / Nr. 7, and when, towards the end of his 1893 vacation, Mahler made an unsuccessful attempt to begin work on the finale, he commented to Natalie Bauer-Lechner (NBL2, 28; HLG1, 276 (revised, with editorial underlining)):

After attending Hans von Bülow's funeral service on 29 March 1894 Mahler sketched a setting of Klopstock's opening stanzas, followed by an orchestral interlude that included a reference to bb. 23–4/59–60 from Urlicht (=S5.4).¹ This allusion does not appear at this point in the final version of the movement, and the editors of NKGII conclude that its appearance in the sketch 'is probably not an indication that Mahler had already decided to incorporate the entire song.' (vol. 2, 6, 94); nevertheless its presence in this early sketch does indicate that at some level the song resonated in Mahler's imagination as he notated his first ideas for the finale and moreover, there is a reference to precisely this phrase in the final version of the movement, at bb. 640ff. A notable biographical source, the memoirs of J.B. Foerster, offers some interesting evidence about this chronological conundrum (JBFDP, 406; translation from NKGII.2, 95):

If Foerster correctly recalled the events of 1894, the reference to the 'sketch' in this account seems to suggest that the decision to include Urlicht was made between 29 June 1894 (the completion of the composition draft of the finale) and, at the latest, 25 July (the completion of the orchestral draft of the movement ([OD5]) (NKGII.2, 7, 95). However, in the partial manuscript copy of the work prepared in the autumn of 1894 (ACF1), the scherzo is placed second, and the Andante third, although both the handbill for the partial première in March 1895 and the reviews (see HLG1, 319–21) make it clear that the movements were played in the now familiar sequence. One might also note that in the complete autograph full score (AF2; completed on 18 December 1894) only Urlicht is numbered in ink: '4'. The remaining movements are all numbered in blue crayon and the fascicle structure is such that the Andante and Scherzo could have been in reverse order when the manuscript was originally prepared, and placed in their present sequence only at a later date; the fascicles were in the final order when the pencil foliation was supplied. Whether these features should be interpreting as evidence that even as late December 1894 the number and sequence of movements was still uncertain is a matter for conjecture: in the absence of crucial primary sources the chronology remains unclear. However, in October 1901, at the time of the Munich première of the Symphony, Mahler, in conversation with Natalie Bauer-Lechner, recalled his indecision about the order of movements (NBL2, 169):²

This seems to be an important statement of principles, that (a) similarity of mood and/or tonality was undesirable between adjacent movements; but that (b) it was possible for an extreme contrast in mood between adjacent movements to be troubling. In the case of the Second such considerations led the composer to contemplate a different ordering of movements and it was apparently the first principle that took precedence in his decision making process: Original and final key sequence C minor - A Alternative sequence C minor - C minor - A Apart from the lack of mood and strong key contrast between the third and fourth movements in the alternative sequence, it may be that Mahler was also doubtful about beginning the work with two movements in the same key and mode: more than ten years later it was clearly again the crucial issue behind Mahler's decision to reorder the inner movements of the Sixth Symphony. Movement Grouping All published editions and issues of the full score agree in the their instructions placed at the ends of three of the movements: a pause of at least five minutes after the first movement, and the last three movements to be played without breaks. This suggests a movement grouping that is not wholly congruent with those implied by the programmes: the January 1896 programme associates the first three movements, but does not explicitly link the fourth and fifth together; the March 1896 programme links the second and third movements together (as intermezzi) and tacitly links the fourth and fifth movements. The layout and text of the 1901 programme is explicit in its tripartite division with Urlicht being part of the central group of three intermezzi and this finds an echo in a letter from Mahler to Julius Buths (25 March 1903 ) in connection with a forthcoming performance of the work in Düsseldorf (GMB, 315–6; GMSL, 269):

In view of these comments it is perhaps worth noting that the layout of the handbill for Mahler's last performance of the work, in Paris in 1910, also seems to associate Urlicht with the scherzo rather than the finale. Nevertheless Mahler made no changes to his instructions in either the study score (1906) or the printer's copy (APFpr) for the third edition of the full score (1908–9) (See NKGII.2, 18, 106 for a discussion of this issue). The peregrinations of the 'off-stage' brass instruments in the finale are complex, and, in the case of the trumpets, not always clarified in the score. The four horns are first heard 'off-stage' in b. 83ff., before making their way on-stage from b. 93, in readiness for b. 202ff. where they take parts 7–10 (their inclusion at this point was first adumbrated in an autograph revision to ACF2). They resume their off-stage position from b. 252 in readiness for bb. 447–71, during which the verbal instructions imply yet more movement: at the outset all are 'in die Ferne' and 'Links aufgestellt', but in b. 461 they should be 'sehr entfernt'. After bar 471 they return to their positions in the main orchestra, again taking parts 7–10. There is some uncertainty about exactly how many trumpets the work requires in the finale. The rubric at the start of the movement lists six on-stage trumpets in F and four off-stage trumpets in F (but see below) of which two parts may be played by on-stage trumpets 5–6, and an autograph addition in ACF2 instructs them to move off-stage at b. 323 to double the offstage parts (one of which is for trumpet(s) in C) in bb. 343–380. However Mahler seems not to have grappled with the problem that in terms of stage management it would be difficult for trumpets 5 and 6 to be doubling the offstage parts in b. 380 and playing on-stage in bar 385. The first edition of the printed parts (PO1) - whether intentionally or in error – omits bb. 343–380 from the parts for tpt 5 and 6 (though a pencil annotation at fig. 21 in APO tpt 6 reads 'go to other part' which implies they may well have moved off-stage in Mahler's 1908 performance in New York; one wonders how this move might have been managed). A further contradiction emerges later in the movement. Despite the fact there must be a minimum of two trumpets placed permanently off-stage, after b. 417 in the printed scores Mahler needlessly instructs that onstage trumpets 3 & 4, as well as 5 & 6 take up places off-stage in preparation for the four-part off-stage trumpet writing of bb. 452–71 (see ACF2 for a summary of the relevant annotations to that score). This lack of clarity over numbers seems to stem from a desire to minimise the number of additional trumpets required, but, if so, this is rather undermined by the demand that from bar 689 the six on-stage parts should be 'mit Verstarkung'. This apparently implies at least twelve on-stage trumpets at this point. The printed part set resolves these ambiguities: the parts for on-stage trumpets 3–6 do not require the players to move, or to play bb. 452–71 (and there are no annotations in APO to suggest Mahler's practice departed from the letter of the parts), as the whole passage is given to the four off-stage trumpets who then move on-stage to provide the required doubling in bb. 689ff., with the six-part trumpet writing of the passage skilfully redistributed amongst the four doubling instruments. SWII: Gustav Mahler, Symphonie Nr. 2, Sämtliche Werke, Kritische Gesamtausgabe, Band II, ed. Erwin Ratz (Vienna: Universal Edition, 1970) SWSupp1: Gustav Mahler, Totenfeier, Sämtliche Werke, Kritische Gesamtausgabe, Supplement Band I, ed. Rudolf Stephan (Vienna: Universal Edition, 1988) NKGII: Gustav Mahler, Symphonie Nr. 2, Sämtliche Werke, Neue Kritische Gesamtausgabe, Band II, ed. Renate Stark-Voit, Gilbert Kaplan (Vienna: Universal Edition/Kaplan Foundation, 2010) This superb edition offers an exemplary critical commentary, including detailed source descriptions for those documents relevant to the editorial process. It is in two volumes: the score (NKGII.1) and the textual volume (NKGII.2). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mahler’s “Totenfeier”: a symphonic poem? –

A Postscript From sketches to autograph full score – Outline Diagram From autograph full score to ACF1– Provisional Stemma Production of printed scores and parts – Provisional Stemma |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2258-0267

©

2007-21 Paul Banks | This page was lasted edited on

24 June 2021

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2258-0267

©

2007-21 Paul Banks | This page was lasted edited on

24 June 2021